Blooms boiling over the trellis,

blue, purple, ultra-violet

Appear in dew of new sun

and drown in ink of night,

Drop to a carpet of color, fading

memories of mornings’ glories.

Sam1-4 wrote from afar

(I'd never met or heard of him)

in a box of sandals, blue,

A note, quite brief, which simply said,

'Packed with pride by Sam1-4'

(sweet he thought that I should care),

And, mused I, that Sam must be

a kind and gentle working man,

perhaps a sort I'd like to meet,

Though almost certainly he speaks

a tongue quite strange, unknown to me,

like bird song mixed with clicks and halts.

In my mind I greeted him,

"Hello, dear Sam1-4, good soul!

How pleased I was to get your note."

And he replied, "My dear new friend!

How fine it is to hear from you!

You are the first one to reply."

And so we garrulously spoke

on many topics, low and high,

women, books and moons above,

Until the man from Porlock knocked,

(the interruptor famed of old)

who broke apart my reverie.

I know that Sam1-4 and I,

shall speak no more, and I shall miss

conversing with this distant friend,

Who, if were found, could only speak

with smiles and tears and waving hands,

as he outside my head would be.

He saw the Mona Lisa on

an ancient wooden power pole

one San Francisco chilly day,

Surrounded by a murky fog,

a thing of strange consistancy,

a soft translucent wall of air

Pushed aside his probing hand,

he tried but could not touch the child,

still smiling through five hundred years.

A crowd assembled, curious

at his pale arms grabbing air,

"What are you doing?", asked a girl.

"Don't you see?", the man replied,

"Her face, her lips, her guile and charm,

the slyness in her gentle grin?"

A boy, quite small, ran to the post,

and said, "I see a poster there.

It says, 'Reward for my lost cat!'"

They smiled and laughed, not at the man

but just the gentle joke of it,

as thickening fog spread round about.

He turned and moved into the crowd,

now silent, gray as lumps of clay,

they fade into the darkened day,

While, down the street, the boy cried soft,

"Here, kitty, kitty! Here, kitty kitty!"

The man, alone, remained distraught.

He turned and faced the splintered post,

which smelled of creosote and tar,

and saw that she remained aloft,

She smiled at him and knew his soul,

his secrets, sins, and failed loves --

naked, though still clothed, he shrugged,

He walked away, his eyes held low,

and, guided by low booming horns,

he found himself at water's edge,

And took the ferry waiting there

across the cold and choppy bay

to an empty house so far from her.

Chaos writes with windy pen

on dunes of sand and frothy sea,

cirrus clouds aloft, and then

Erases all before we see

the transient text that's hid therein.

She makes a breeze beneath our door

and tricks us with her icy chill,

freezing feet both rich and poor,

Whispers with a voice quite still,

while scuttering frost along the floor.

Carefully mounded garden leaves

spout up in twisting jets of air;

she throws them up into the eves

And casts them down upon our hair;

confusion reigns while she deceives.

She moves the air in many ways,

a gentle touch, a typhoon's blast

slanting rains from storms just past;

She whimpers, rages, laughs for days,

the words she babbles forth don't last.

So, though the message can't be read,

still, it's plainly understood,

that Chaos birthed our world and said,

"My work is neither bad nor good,

in fog you stumble, then you're dead."

His mother told him many times a bird most striking had appeared in the window at his birth, How calm she felt the last hard push which shot him forth into the world, as red and yellow feathers flared.

... In the woods, the fire burnt out, an old man left the child there with tales of gods aflight. The boy had felt the ashes, cold, startled at some thrashing wings, seen glints of color in a tree. ... His guide was pointing to three birds, flying through a sulfurous cloud at craters's lip where they fell dead; The hiker sensed a whir and saw at vision's edge a brilliance fleeing molten rock. ... On his walls were pictures -- quetzal, peacock, red macaw, golden pheasant, scarlet ibis; His questions lay in ancient myth, memories shimmered through his day, his dreams at night kaleidoscopic. ... She was above him, rouge and gold, nuzzling hair with avian kisses, feathers falling over him, And sang, "Miss you so, love you so!" He felt her answer brush his cheek, his last breath smiled, and then he flew.

He never found a calendar

he couldn’t keep —

Museums, Mens’ clubs,

Bornholm, Bay homes,

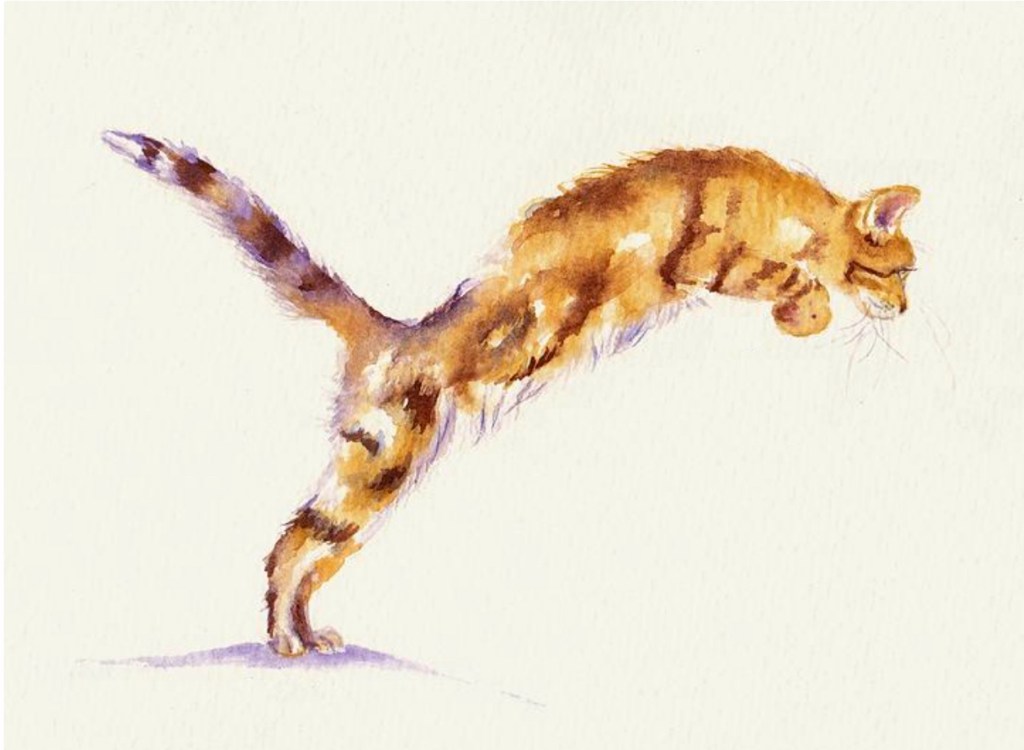

Cathedrals, Cats,

Gas stations, Radio stations,

Candies, Cookies,

Doctors, Drugs,

Insurance agents, Actors’ reps,

Pols, Celebs,

Pinup girls, Weber grills,

Alliance Française, Esperanto Youth,

Night school, Preschool,

Elder Host, The US Post,

“Dates, steaks and apricots,

shipped to your door”,

“Pigeons & Crocks,

and much, much more”,

Endless lists,

guarantees

that time persists.

475

675

565

585

574

576

575

The Swede told him Danish

was so difficult

its own people can’t learn it

until they’re five.

As he pontificated,

his very young children

happily played house

with babbling little Danes.

How can that be? asked the man.

Oh, quite easy, replied the Swede;

Until they’re five

they just speak Scandinavian.

The report said,

“Mildly deviated septum,

otherwise normal sinuses.”

He remembered age four,

excited, impatient,

Standing 3 steps up

a concrete porch,

Holding a celluloid tube

of tiny candy balls.

He’d seen older kids do this,

even sharing once,

And now his chance

to pry the plug

With wild fingers,

only to spill everywhere —

His haste-driven dive

to reverse the effects

Of gravity on plunging spheres,

found his nose resting

On the sidewalk below,

where he bellowed bad luck.

Soon, clinging

to his mother’s neck,

As she wiped

his blooded face,

He complained only

about broken fortune.

His nose was quickly forgotten

for a lifetime,

Until x-rays penetrated

his memories,

Of sweet loss rolling away,

yet still desired.

He was 4 or 3,

at the edge of memory,

When he saw a dead possum

in the road.

For 80 years it visited

his thoughts;

Nothing before —

not a mother’s loving gaze,

not a father’s good cheer,

Just a tail carelessly touching

a bloodied nose,

And two button eyes, staring

at god, at him,

at nothing.

Egg tottering,

nest ruptured by careless wind,

future flight’s dashed promise,

embryonic wings unformed.

Bird ghost’s

first and last airborne arc,

parabolic to slate below,

shattered shell and yellow stain.

Surprised child

stops, curious, then home

crying in fear, chased by

angry mother cawing grief.

He saw, on his morning walk,

a house with cobalt walls

and pink eves,

But, on drawing closer…

the eves became brown

and the walls, gray.

He thought about imagination

and the word ‘image’

almost within it.

He had, as always, a goal in mind,

but this route was chaotic,

random with bias.

He chanced on a stick

in a gutter,

long, straight, lanceolate.

And imagined two spears,

one pink,

one cobalt,

Except the pink was really

like a filet

of wild Atlantic salmon,

And the blue was

like sparks of

violet and green.

He saw two knights

rushing each other,

red pike, blue pike…

And stumbled at the sign,

his goal,

“Matmor Rd”.

Mata mor,

mata moro,

kill Moor.

He drifted to the Crusades —

his fifth-grade teacher

described their futility;

Yet, he later read

about the 200-year

Kingdom of Jerusalem,

Probably not so futile

to the knightly order

for a long time.

She also remarked

on the Moorish failure

in Iberia,

But, the Caliphate endured

600 years, three times

my country’s age.

Images returned —

the Knight Templar,

the Saracen knight;

He thought

perhaps that

was the whole point,

To impale each other

on beautiful lances,

salmon and electric,

Despair of yellow if you wish —

The taint of

choleric bile,

Midas’ daughter,

snow pee,

jaundiced eyes.

While Orpheus’ golden lyre

went to Hell and back,

sunlight echoed on dayend clouds,

towheads ran on Baltic sand,

dandelions colored my hand.

Jacob’s stairs still ascend

— presumably to Heaven —

But who waters the geraniums?

Early morning fogs rose from the river. He waded through an eddy of warmth swirling slowly between bank and goal, a heavily wooded island, cloud hidden, Spanish mossed limbs penetrating opal curtains. He felt time evaporate a hundred million years as he entered the past earth. and knew the river damp smell was once familiar to a dinosaur, that nothing had changed, that his particular world's sights and sounds were truant. Reaching shore, he had no idea how close he was to the nest of guarded eggs, as she burst forth through fog, the Great Blue Heron, screaming in the very rasp of God, a cry so terrible that he became a wee twitchy creature, scurrying to evade scaly winged masters of this new world.

The Demon-Casters of Asilomar,

in the great lodge room,

huddle before fire,

Ess-word mutterings float,

"...sssalvation...,

...sssatan...,

...ssssin...",

potent, frequent

"...Jesssusss...".

Bowed backs as

shields,

Stares as

needles, knitting,

White thin lips as

prophet, knowing,

But no

blue eyes on the

lurking heathens

(who suck your soul),

No

flirtation,

temptation,

touching the

unwashed.

This is a joyless,

serious pursuit,

Saving the world.

I worked nights in Brazil, photographing stars. Coming home one morning, I found the neighbor kids gathered around the curb. All year, a trickle of water ran beside it, starting from a neighbor’s farm and moving down through the prosperous community below, eventually draining into the Rio Potengi.

ran beside it, starting from a neighbor’s farm and moving down through the prosperous community below, eventually draining into the Rio Potengi.

“What’s up?”, I asked.

“Fish!” they answered.

They were on their knees, giggling, hands in mud and water. I walked over, expecting floating toys of sticks and leaves, but saw little flashes of color. A child’s cupped hands held a small, brightly hued fish darting in a bit of water.

I knelt beside the rivulet and saw hundreds of tiny finned creatures slipping through fingers of little people delighted by their beauty.

I lived a few degrees from the Equator. These were tropical fish, the real thing. They weren’t in an aquarium in a doctor’s office. They lived free in their home, my gutter.

A ripple spreads from a Kansas tornado,

and the wings of an Australian butterfly skip a beat.

That would also be chaos.

The image is the Australian Amnesty Butterfly — click on the link to learn more.

Living in Natal, Brazil, was time travel. Evenings, we strolled and conversed lazily, danced at the social clubs, visited the dying in front rooms, surrounded by friends, and went to the barber for a shave — hot towels, straight razor, funny jokes and a rubdown, all for a dime, like an old movie.

Once, I was having a haircut. A man with no legs came in, selling lottery tickets. He maneuvered on a roller board, head about knee high. Everyone knew him. A few bought tickets, and he moved past the line of chairs where he waited. Why was he still there?

The barber to my right finished a guest and turned to the lottery agent. “Same as ever, José?”, who nodded. In a fluid motion the barber lifted him from board to chair. Question answered — a customer, like everyone else, and a frequent one.

A sheet billowed out and was pinned behind his neck, steaming cloth applied, and the conversation continued without break. A few minutes later, towels removed and face skillfully shaved smooth and clean, followed by a brisk massage. Second puzzle — the barber was in no hurry and the next patron seemed happy where he was. Gossip, sports, politics, weather flowed as ever in that global mens’ club. José smiled and chatted, a member in full standing.

I was done. My barber spun me about to face the grand mirror on the wall of every barbershop. “What do you think?”, “Looks great!”, universal query and response. My eyes strayed to the salesman’s reflection, head level with mine, great sheet before him down to floor. Puzzle solved. José sold them lottery tickets and a chance at riches. They sold him a shave — and added legs for a few minutes every day.

Ten years ago, I moved from Salt Lake to California and lost neighbors, views, streams, opera, a packet of poems from 1996, and so much more — but, last week I stumbled across the poems.

It was exhilarating and emotional, like coming out of a suicidal coma and finding life is wonderful after all!

Well… a little like that. Maybe just a touch, for this very specific event.

Hmmm… To tell the truth, life has actually been quite interesting this last decade. The discovery was a bit of a rush, a stimulant, an exhilarant, a mood elevator.

A better metaphor: Imagine that you discover that the little toe on your right foot, which you thought you’d chopped off with an axe 10 years ago, has all along been folded in a peculiar fashion under the other four toes, and that a little clever autochiropractic manipulation pops it right out — now when you prance on naked tippy toes around the house, everything feels just right.

More like that, perhaps, than the suicidal coma.

See them here, if you wish, but, for the most part, they are raving doggerel. They are purposefully scrambled. Do not try to find any thematic continuity in their arrangement.

You could compress data on your computer, Or you could turn, red-faced, and close the hole in your pants, Or you could move fast from here to there. Take your pick, small, medium, or large.

We’re sitting in the living room, and Dad asks, “What was the name of that bread”?

“What are you talking about?”, says Mom.

— “That sponsored the ball games”.

— “What ball games”?

— “On the radio, when I came home from work”.

— “You don’t work anymore”.

— “When I worked — past tense”.

— “That reminds me… Once you came home from work and sat down in the living room, this room right here. It was late, you were tired, the TV wasn’t working, and you said, ‘I think I’ll go to bed’. And I grabbed you by the hand. You said, ‘What’re you doing?’, and I said, ‘I want to show you something’, and I took you into the kids’ room, and I woke them up and said, ‘Hey, kids, I want to show you something. This guy here, he’s your father’! Well now, they thought I was crazy”.

— “Home Farms”.

— “Home Farms”?

— “The bread. It was white”.

— “What does that have to do with my being crazy”?

— “They did the ball games. You asked me why I always bought it. It was the ball games — I wanted to show my loyalty”.

— “And for that you call me crazy”?

I put my book down, and look at Dad. He’s wearing a half paper plate wedged between his glasses frames and head. He’s shading his eyes from the floor lamp, and told me years before that he found it better than wearing a hat in the house. I realize that, tonight, I’ll never read this book. The story I’m part of demands attention. It’s compelling, droll, insane. It’s exhausting.

Time for bed.

Part 1

Old folks die noisy deaths. This is not the received wisdom of youth who firmly believe in the silent slide to oblivion "He just closed his eyes, and was gone!" she gushed with a smile, As though describing a child's first steps. The truth is Great-aunts drop casseroles onto hard kitchen floors, as their chests burst, Widowers knock over tables lurching from bed clutching their throats, A farmer scolds his dog, -- gone 40 years -- for chasing sheep, And the mother rips tubes from her arms, cursing the nurse for poisoning her.

Part 2

The dying man hears the loudest noise. He carries from birth a metal bowl into which drop steel balls, at odd moments, unexpectedly. He walks alone down a long crystal arcade, lined with glass cabinets. The bowl becomes heavy and he grows frail. He pitches forward and the perfectly elastic spheres bounce everywhere, a cacophany of clack-clack-clack and breaking glass. He lies, clinging to the sounds, life oozing from his mouth with each moan, Not fully gone until silence follows the last tap.

PINK I just saw an old art joke --

"PINK" in purple ink --

A T-shirt on a sad young girl

Stalking out of (what else?)

A gallery, and thought

Of the drowning man

Trapped

Beneath a grate

An inch beneath the surface.

He breaths through a straw

Penetrating the screen,

Will live only if he

Inhales slowly,

Calms his anxiety,

Relaxes until

He dies from hypothermia,

Or -- if in the Carribean or

The Gulf of Cortez --

From starvation,

But never from thirst

Or the color pink.

Lumbering, misshapen, looming tree, no symmetry, favorite by far, visible for miles in my flat land, shading two unlikely litter mates — dog, ugly happy thing, flabby jowls, stubby legs, marching by sister cat — two same-day born beings, carried box to box by mothers, confused, unsure finally of offspring, form & laws of inheritance — he marches beside that creature dearest in his life, who in turn leaps into air, runs beneath dog belly, rolls in plowed earth of the great shared field — these three allies standing guard against sun, assassins, and tiny jewels floating in dusty rays.

Lumbering, misshapen, looming tree, no symmetry, favorite by far, visible for miles in my flat land, shading two unlikely litter mates — dog, ugly happy thing, flabby jowls, stubby legs, marching by sister cat — two same-day born beings, carried box to box by mothers, confused, unsure finally of offspring, form & laws of inheritance — he marches beside that creature dearest in his life, who in turn leaps into air, runs beneath dog belly, rolls in plowed earth of the great shared field — these three allies standing guard against sun, assassins, and tiny jewels floating in dusty rays.

My friend, Mike, is a master virtual guitarist, perhaps the best in the world. At times, his eyes half closed, lips slightly parted and smiling vaguely, he twitches his fingers in a barely perceptible way, and I know he is performing at Prince Albert Hall. And Fani, the master aficionada, gazes dreamily at her musician and listens with an invisible rose behind her ear.

Recently, I drove oceanward on a small 2 lane highway leading, in a circuitous but ultimate way, to San Francisco. I passed an intersection which seemed familiar but also vague and unspecific. I puzzled and began to assemble a picture from fragments of memory. I had arrived in my new town 8 years ago and wanted to explore. I drove west on a country road towards the Coast Range through the rural flatness, curious only about where I was. After a few miles, I found myself in rolling hills with homes, children, pets and small farms. I was happy with this discovery, as my wife found the levelness of our new area depressing, and knew that my report of what lay nearby would cheer her. The road gradually turned and came to the very intersection I had just passed moments before.

Unfortunately, when I looked in the direction of this dimly recalled population, I saw only a thin forest of valley oaks and eucalyptus, no undulations, no ersatz Shangrila in the depths of Yolo County. I now knew that there should only be flat farmland all the way to the mountains edge. I had fought to put this puzzle together, and must have fused memories of events from long ago, perhaps in Salt Lake City, perhaps in Toronto. I had rationalized a sense of deja vu which, in reality, was false. I have a fertile imagination, and have done this before.

I had occasion to pass the same point several times since, and each time had the same unsettled feeling of having been there, went through the same process of assembling memories, came to the same depressing conclusion, and worried about the gradual decay of my brain. Then, a week ago, Laura accompanied me to the coast, and as we approached the intersection, I told her the story about my imaginings and poor memory. As we entered the intersection, I looked left. Previously, I had only done this after the fact. This time, I had a clear view up the exit road into the distance, and saw — rolling hills, houses, horses, children playing, with a sparse forest on both sides which fused after we passed into a green panel obscuring a remembered event I now know was real and unimagined.

My wife does not think my memory is bad, but she does think I am mad.

A five-minute walk from my workplace lies a red building of great mystery. It is worthy of capitalization: The Red Building. I have walked around it hundreds of times in eight years and did not see it the first seven. It is accessible but guarded by taller structures. No one enters or leaves. A view through the windows shows abandoned lab benches, hoods and offices, covered with dust. No bodies are visible, at least not directly. It is unacknowledged — the campus map pretends it is a wing of an adjacent edifice, which it is assuredly not. It is a place of someone’s fear, an unsettling enigma, a place of desperate ignorance.

Today, I visited bees, perhaps a dozen varieties, including a 4 foot ceramic one of alien and exciting coloration. “Welcome to our garden!”, said a kindly man of academic beard, who warned of little cups of colored liquid on the paths. I avoided them adroitly, but did notice varying numbers of dead bees therein. Bee Haven, while an idyllic refuge for sober hard workers, capitally punishes its drunkards.

My son, Aelric, was an artist for four years and has since graduated to other pursuits (our and the world’s loss!). He was brilliant, creative and fast. His pallette was primaries plus black and white, mainly acrylic, occasionally tempera.

My son, Aelric, was an artist for four years and has since graduated to other pursuits (our and the world’s loss!). He was brilliant, creative and fast. His pallette was primaries plus black and white, mainly acrylic, occasionally tempera.

He used only a large one-inch flat brush and a small round brush whose handle was employed more than its fibers. He painted canvas, masonite, all kinds of paper, and even sticks. His works can be found on walls, desks and cards all around the world, as well as a few right here.

He reveled in color and was fearless in its application, with no pretense of representation. The act of painting was purely performance — he loved his audience and kept a constant commentary as he layered with abandon.

He set only one rule — he was done at the request of the audience. Without this subtle intervention, the continually added color gradually merged into an amorphous mass of gray.

Victor Vasarely gave us Op Art, Andy Warhol, Pop Art, and Aelric Kofoid, Stop Art.

Do not let the wild cows of Highway One

seduce you with their siren moos.

Notice how they cling to a vertical wall,

daring you to peer over the edge

at their ragged victims on the beach below?

I’m in a bright, shiny, synthetic mall, surrounded by money and Muzak, while outside are blue skies and brilliant sun, and I think of La Jolla tide pools, swimming with my brother through clouds of confused anchovies smashing into our legs in a frenzy to return to deeper waters before the tide drops even more and traps them, where they don’t want to be.

Not a day went by that my parents didn’t hate Eureka. The cold, the damp, the drizzle, the smells of fishing and wood mills were utterly foreign to their San Diego-driven view of the universe. When I breath its sulfur and anchovie essence, I once again race my bike through a stinging cloud of droplets, excited, happy to reach Stubby’s birthday party in the mud and slippery green grass.

Not a day went by that my parents didn’t hate Eureka. The cold, the damp, the drizzle, the smells of fishing and wood mills were utterly foreign to their San Diego-driven view of the universe. When I breath its sulfur and anchovie essence, I once again race my bike through a stinging cloud of droplets, excited, happy to reach Stubby’s birthday party in the mud and slippery green grass.

Crows, I am told, can tell us apart with exquisite ease and, of course, have no problems with each other, whereas we — even the most skilled corvidologists — are unable to distinguish one of them from another in any subtle and automatic way. Except for me — my beautiful crow is the one that places the walnut in the road when she sees me rushing to work, caws and flaps in the air as I pass, and glides gracefully to the meats exposed by my tires. She is confident of my intentions and is, in turn, faithful. She knows me regardless of conveyance, and ignores all other vehicles, which would as soon hit her as the nuts. It is a strange affection and if I were a crow, I would go out of my way to dine with her as often as possible.

Some days, all Bornholm walls are the summer sun’s own gold, baked deep into gypsum coat, warm just by sight.